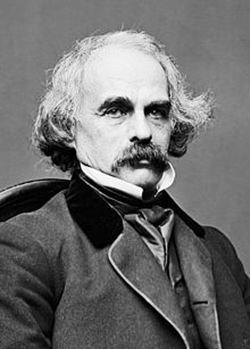

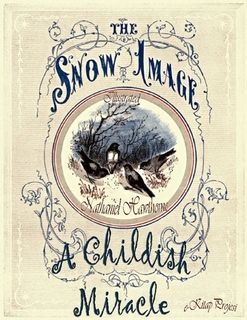

Some of Nathaniel Hawthorne's early stories for children which appeared initially in juvenile magazines ended up in collections of stories for adults. Such was the case with "Little Annie's Ramble," which appeared first in Youth's Keepsake and then, a few years later, in the first edition of Twice-Told Tales. Other stories took the reverse journey. They were written and published for adults, but were reprinted individually with illustrations for the juvenile market. One such story was "The Snow Image: A Childish Miracle," written for adults and published in 1851 in The Snow Image and Other Twice Told Tales. By the early 1860s, it had been published separately as an illustrated children's book and continued in print as such for many years, aimed at the 6 to 8 year old reader.

|

|

|

|

Preface (About the Book)

Some of Nathaniel Hawthorne's early stories for children which appeared initially in juvenile magazines ended up in collections of stories for adults. Such was the case with "Little Annie's Ramble," which appeared first in Youth's Keepsake and then, a few years later, in the first edition of Twice-Told Tales. Other stories took the reverse journey. They were written and published for adults, but were reprinted individually with illustrations for the juvenile market. One such story was "The Snow Image: A Childish Miracle," written for adults and published in 1851 in The Snow Image and Other Twice Told Tales. By the early 1860s, it had been published separately as an illustrated children's book and continued in print as such for many years, aimed at the 6 to 8 year old reader.

A Childish Miracle

An afternoon of a cold winter’s day, when the sun shone forth with chilly brightness, after a long storm, two children asked leave of their mother to run out and play in the new-fallen snow. The elder child was a little girl, whom, because she was of a tender and modest disposition, and was thought to be very beautiful, her parents, and other people who were familiar with her, used to call Violet. But her brother was known by the style and title of Peony, on account of the ruddiness of his broad and round little phiz, which made everybody think of sunshine and great scarlet flowers. The father of these two children, a certain Mr. Lindsey, it is important to say, was an excellent, but exceedingly matter-of-fact sort of man, a dealer in hardware, and was sturdily accustomed to take what is called the common-sense view of all matters that came under his consideration. With a heart about as tender as other people’s, he had a head as hard and impenetrable, and therefore, perhaps, as empty, as one of the iron pots which it was a part of his business to sell. The mother’s character, on the other hand, had a strain of poetry in it, a trait of unworldly beauty—a delicate and dewy flower, as it were, that had survived out of her imaginative youth, and still kept itself alive amid the dusty realities of matrimony and motherhood.